The Met’s China show is a stunning curatorial achievement, featuring 300 years of Chinese fashion and European and American designers’ appropriation of it. The show spills over from the costume gallery into the Asian galleries — including one of my favorite Met spaces, the Astor court, a replica of a classic Chinese scholar garden. Here’s, it’s transformed by a gargantuan moon, a reflective floor and the sound of rain. The temperature was just a few degrees cooler than the rest of the exhibit, perfecting the illusion that I had stepped into a night-time garden — tho this one was filled with Peking opera costumes reinvented by John Galliano and Maison Martin Margiela.

Too lazy to write a post on a holiday weekend, I pulled out a stash of carbon-copy letters written by my twice-removed predecessor in the 1970s and 80s. Thirty or forty years later, editors encounter the same issues with authors — but most of us don’t write about them quite so eloquently. Can you match this list of classic author / publisher issues with the excerpts below? Answer key at bottom, along with a few more great pics of Chinese-inspired couture.

- a. Is the publisher doing enough to market the book?

- b. Complaint about unfulfilled publisher obligations (in this case, when royalty is due).

- c. Incomplete manuscript — text with no art.

- d. Investment in color production and printing.

- e. Errors in the instructor’s guide / answer manual.

- f. Need to stick to budget on illustrations.

- g. Yes, we really do need a coherent, complete instructor’s guide.

- h. No more book ideas before the first one is finished.

- i. Manuscript is too brief.

- j. Project is terminated due to late manuscript.

- k. Correcting errors at proof stage.

- l. Why royalty reverts to the original rate at revision.

- m. Sloppy manuscript.

- n. Manuscript should be written one chapter at a time, not “all at once.”

- o. Manuscript is too difficult and academic.

- p. Manuscript is late — again.

- q. Author alteration charges from changes during production.

1. We intend to make every correction we can pinpoint in terms of factual error, in terms of wrong captioning, in terms of misleading layouts which defeat the purpose of the book. We will not at this time confuse improvements, nuances or unattractiveness with error. Those irritations will have to await the next edition….It will no doubt require all your restraint to help us in this current endeavor.

2. We cannot give an incomplete manuscript to a designer. We have had every intention of bringing in a designer once we have 100% of the manuscript. That would mean we would need all the illustrative material. If some material is unavailable and cannot be obtained, then we either must replace it or drop it from the book. One of the key areas of confusion, I believe, has to do with the definition of the complete manuscript. Particularly in the case of a book heavily dependent on artwork, the manuscript must include all of the artwork to be used in the finished product. For the purpose of book design, the art selection must not only be complete, but it also must be keyed to the section of the book in which it is to appear. In short, the book designer has to know which pieces of art go where.

3. From a practical point of view, color was not originally considered for this book, and should not now be introduced — for two reasons: it is very expensive and will have a profound impact on our pricing structure. Secondly, at this juncture, it would seriously delay the project, which is what none of us want to do.

4. Regretfully, I must selfishly maintain that our promo budget has to stretch over an entire year and cover a barrelful of titles. Yours does get preference because we feel it’s a winner.

5. The publisher’s cost commitment on a new edition is precisely the same as prevails for a new book. We must make an investment in editorial and production staff time. We need new artwork, a new design, new composition and a new cover. All of these items only come into play when we do a new book, and not when we simply do a reprint. So, with all our authors . . . we have followed the same contractual arrangement as reflected in our missive of September 6.

6. Apparently you haven’t read the contract carefully or recently. It’s very clear. For your convenience I’ve indicated the operative clause in this case.

7. We all know the book is terrific, but that’s the way teachers are; the guide helps get adoptions. The guide was supposed to be here no later than September 15. Instead, we have in-house 25 pages which XXX has much difficulty understanding. I would settle — in fact, I would prefer — a tightly written guide of 50-60 pages that we could quickly produce and distribute almost immediately.

8. I’ve come to the sad conclusion that the answer book situation has lost us quite a few adoptions. We have around 500 answer books in inventory. We could replace these with a corrected version at a cost in the neighborhood of $450. I believe that the book division shouldn’t be held responsible for the answer book dilemma, that this responsibility belongs to the authors. What I propose is that we charge off costs for production of 500 corrected answer books against author royalties. That, at least, would be a painless way at your end, and would no doubt be covered by the next royalty period at latest.

9. I respect you as a professional, and since this is probably not the last project we will work on together, I know I can be honest with you. It’s been a long time since I received manuscript in this condition (single spacing, different color inks, illegible handwriting, no indication where captions begin and end, etc.) No publisher, or editor, should have to accept this . . . other publishers would have had authors pay to have this retyped so that it is suitable to send to the typesetter. . . . The manuscript pages were not numbered consecutively. What if the manuscript had been dropped on the floor?

10. We are willing to make an investment in illustrations as required so long as we work these costs out up front and have control over the total investment. Our aim is to maintain a cap on costs so that we are not forced to price the book so high that we price ourselves out of the market.

11. Given your hectic schedule, we had all thought a monthly chapter submission schedule would be in order if we were to hit our deadline next February. I have to be from Missouri [editor’s note: Missouri is known as the “show-me state”] on your current approach. Our experience with very busy people is that across-the-board efforts never result in on-time delivery.

12. The text appears thin. At times it seems more an outline than a full-fledged book. Maybe you’ve consciously decided on a thin book. By thin, I mean a book that looks like about 130 pages, about half or more in illustrations. That’s lopsided, by traditional textbook standards. . . . One final, personal point about educators in the nation. Most expect everything to be explicit in the text they’re using. No doubt, you could use this [text] as a framework for classroom activity and weave a lot into the sessions. But we can’t assume that kind of creative teaching in our potential audience.

13. While this strikes me as a “heavy” book in the sense that it’s very high-level, management-serious and strictly no-nonsense, I can’t help but feel that a small amount of relief in the form of some charts or prototype documentation might help break up the narrative. It helps sometimes, particularly with readers, practitioners, and librarians.

14. I have it from our production staff that, on at least six occasions, our mutual friend was advised that extra costs would result in a day of reckoning. The screws are really on here and we will have to provide details to author and to management and work out something that will be fair, albeit painful, to all concerned parties. The carefree spending days, I’m afraid, are over.

15. XXX has forwarded to my attention your letter on the proposed book project or projects and I’m responding promptly to avoid any misunderstanding or confusion . . . The collective wisdom supports our original judgement that we give priority to a text on XXXX . . . From our point of view, we feel the truism of first things first remains valid. We agreed on an XXXX book, and we would hope that both parties would honor that agreement: the author to deliver a completed manuscript at the agreed upon date, and the publisher to publish within a reasonable period of time.

16. We’re only bystanders until we get a manuscript. We have now unfortunately moved your project into the gray area; that is, a project about which there is question about its completion. I hope you can tell why I’m pessimistic. What I really need is some form of realistic projection so I can allocate editorial and design time.

17. [Letter dated August 29, 1990] With much regret, we’ve decided we will have to terminate the Agreement dated January 6, 1986, the manuscript for which was due by Jan 15, 1987… You have, of course, an important reputation in your field, and we would welcome having a book from you in our catalog. But, unfortunately, first we need a completed manuscript. Again, good luck in all your endeavors. Cordially, XXX ANSWER KEY

- 4 – a. Is the publisher doing enough to market the book?

- 6 – b. Complaint about allegedly unfulfilled publisher’s obligations (in this case, when royalty is due)

- 2 – c. Incomplete manuscript submitted — text with no art.

- 3 – d. Investment in color production and printing

- 8 – e. Errors in the instructor’s guide / answer manual.

- 10 – f. Need to stick to budget on illustrations.

- 7 – g. Yes, we really do need a coherent, complete instructor’s guide.

- 15 – h. No more book ideas before the first one is finished.

- 12 – i. Manuscript is too brief.

- 17 – j. Project is terminated due to late manuscript.

- 1 – k. Correcting errors at proof stage.

- 5 – l. Why royalty reverts to original rate at revision.

- 9 – m. Sloppy manuscript.

- 11- n. Manuscript should be written one chapter at a time, not “all at once.”

- 13 – o. Manuscript is too difficult and academic.

- 16 – p. Manuscript is late — again.

- 14 – q. Author alteration charges from changes during production.

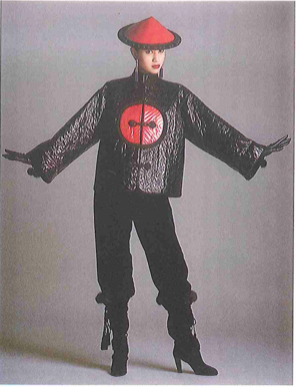

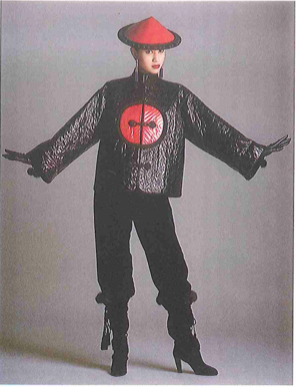

Lots of designers appropriated Chinese styles, but no one did it like Yves St. Laurent in 1977, who modernized the classic looks for late 20th century women.

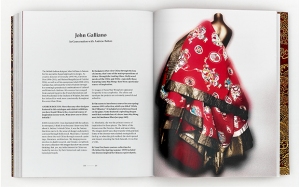

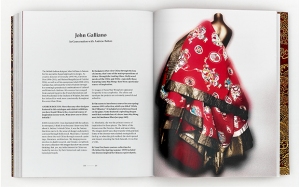

John Galliano has re-invented traditional Chinese styles. The influence is clear but they’ve been transformed into something wholly new.

This image from the Pentagram-designed exhibition catalog shows one of the radical new shapes Galliano brought to the traditional Peking Opera costume.

Craig Green’s work, which I hadn’t seen in person before, was also a revelation.